26 July 2023

The background - In 2016, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (“the Foundation”) licenced to Condé Nast an image of ‘Orange Prince’ - an orange silkscreen portrait of the late musician Prince created by pop artist Andy Warhol – to appear on the cover of a magazine commemorating Prince.

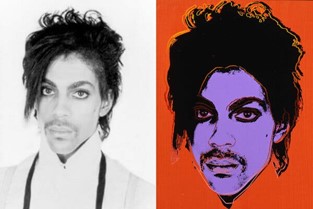

Orange Prince is one of a series of works that Warhol derived from a photograph of Prince taken by celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith. The photograph was licenced by Goldsmith to Vanity Fair in 1984 as an “artist reference for illustration” – a key clause in the licence was that the use of the photograph would be for “one time” only. Warhol was then hired to create the illustration which appeared in Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue. The magazine credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph” and paid her $400.

|

|

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol’s use of the photograph did not end there. In fact, despite the terms of the licence agreement, Warhol used the photograph to create an entire series of images, known as ‘the Prince Series’.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company (Condé Nast) sought to purchase a licence from the Foundation to utilise one of the images in the Prince Series for a special edition magazine to commemorate Prince’s life and career. Vanity Fair paid to the Foundation a licence fee of $10,250. Goldsmith received neither a fee nor a source credit.

The dispute

Goldsmith did not know about the Prince Series until she saw Orange Prince on the cover of Vanity Fair in 2016. Having done so, she immediately notified the Foundation of the potential copyright infringement. In response, the Foundation sued her in the US District Court for a declaratory judgement for non-infringement or, in the alternative, fair use. Goldsmith counterclaimed for copyright infringement.

The dispute ended up before the US Supreme Court, which was asked to consider whether Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph constituted fair use, or on the contrary, whether it constituted copyright infringement.

Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince from 1981 and Andy Warhol’s silkscreen using Goldsmith’s photograph from 1984. Images from US Supreme Court decision: 21-869 Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (05/18/2023) (supremecourt.gov)

The legal position

It is worth emphasising that “fair use” is a doctrine of American law, which permits limited use of copyrighted material in specific circumstances, including commentary, search engines, criticism, parody, news reporting, research and scholarship.

In the UK, “fair dealing” is a statutory defence to an action for copyright infringement, and relates to number of circumstances in which copyright works or extracts from them can be used without permission from, or payment to, the copyright owner. “Fair dealing” has no statutory definition, but is rather a matter of fact, degree and impression in each case. It is, however, more limited in scope than fair use and the concepts are not interchangeable – indeed, an exception that applies in the US may well be regarded as an infringement in the UK. Nevertheless, the decision makes for interesting reading for creatives and those advising them.

In this case, the specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph alleged to have infringed her copyright was the Foundation’s licencing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast. The court was asked to determine whether that constituted a fair use of the original photograph.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a “fair” use, various factors are considered to be relevant including:

i) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes;

ii) the nature of the copyrighted work;

iii) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

iv) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. A key factor also used to determine fair use is the extent to which a new work has a “transformative” purpose, such as parody, education or criticism, versus just being a copy.

The Foundation argued that under the first factor of a fair use analysis, its use of the Prince Series was “transformative” because the works conveyed a different meaning or message than the original photograph and were stylistically different. The Foundation also contended that the purpose and character of its use of Goldsmith’s photograph weighed in favour of fair use because Warhol’s silkscreen image had a new meaning or message, offering comment on celebrity and portraying Prince as a larger than life figure, something not apparent from Goldsmith’s photograph.

The decision

The Supreme Court disagreed, determining on 18 May 2023, by a vote of 7 to 2, that Warhol’s works did not fall under copyright’s fair use doctrine.

The court focused on the specific use that allegedly breached Goldsmith’s copyright - the licence of Orange Prince by the Foundation to Condé Nast - determining that it served the same commercial purpose as Goldsmith’s photo, namely, to depict Prince in a magazine. To hold otherwise would potentially authorise a range of commercial copying of photographs to be used for purposes that are substantially the same as those of the originals.

The court did, however, note that if the Foundation had sought to display Orange Prince in a non-profit museum or a for-profit book commenting on 20th century art, the purpose and character of that use might well have been fair use. It also noted that Orange Prince was not “transformative” and, even if it was transformative, it would not have mattered given the specific use.

It is perhaps unfortunate for onlookers that the court did not offer comment on whether the Foundation’s image of Prince infringed on Goldsmith’s copyright – for creatives and their advisors, this would doubtless have been the more interesting discussion.

The takeaway

The decision and the discussion therein are, nevertheless, worth a moment of reflection. For example, what does it mean now for the Prince Series – can Goldsmith assert copyright and refuse permission to licence the Prince Series at all? What are the implications for other derivative works by other artists? Or, does the decision simply underline the fact that copyright is designed to protect the original artist and her work?

It is also worth thinking about how the case might have been decided, had it been heard in the UK where the fair use doctrine does not apply and the fair dealing doctrine might not have helped. In that event, a UK court would likely have considered whether the Prince Series could be classed as a derivative work (and therefore protected by copyright). In doing so, it would have presumably offered comment on whether Warhol materially altered or embellished Goldsmith’s photograph, such that he created a new original work. It is impossible to predict what might have been the outcome of such analysis, but it is food for thought regardless.

These issues are also worth considering in the context of generative AI, with AI platforms being trained using existing artistic works and then producing new works in response to a prompt, which raises various questions in relation to ownership of the output, infringement and whether the content created is protected by copyright. These are issues with which legislators and courts around the world are continuing to grapple (see our related blog which discusses the ongoing litigation between Getty Images and Stability AI, which may, when decided, provide welcome clarity).

The Supreme Court decision has no legal application in the UK but, nevertheless, serves as a useful reminder for those in the industry to think carefully about copyright and when a work might – and might not - be considered to be derivative. It also serves as a useful reminder to think carefully about the key terms of intellectual property licences – in particular, whether the licence is exclusive, when the rights in question revert to the licensor, and what are the consequences of breach.

Lauren McFarlane, Associate: lmf@bto.co.uk / 0131 222 2939