13 December 2016

In this eUpdate I consider the concept of “the most economically advantageous tender” under (now repealed) The Public Contracts (Scotland) Regulations 2012 and The Public Contracts (Scotland) Regulations 2015, and further I consider contracting authorities’ legal obligations to adhere to fundamental procurement principles of non-discrimination, equal treatment of economic operators, transparency and proportionality against contracting authorities’ legal obligations to treat as commercially confidential certain aspects of economic operators’ tenders.

Introduction

Under the Public Contracts (Scotland) Regulations 2015 (the 2015 Regulations), unlike the Public Contracts (Scotland) Regulations 2012 (the 2012 Regulations), a contract cannot be awarded on the basis of the lowest price alone. So the most economically advantageous tender (MEAT) is now the means by which contracts are, and can only be, awarded.

MEAT

In Tay / Forth Premium Unit Consortium v Secretary of State for Scotland, Lord Cameron of Lochbroom, 19th October 1995, unreported, it became clear that the Secretary of State for Scotland was more concerned with awarding the contract to the lowest price despite the declared intention to award it on the basis of MEAT.

My concern for some time now has been that contracting authorities did not always appreciate that MEAT was not simply the lowest price with a fancy label attached to it. In other words, MEAT, hardly a new concept, has to date remained undeveloped and undefined, albeit quite freely bandied about.

The most immediate questions, however, are whether the 2015 Regulations (i) enhance our understanding of MEAT, and (ii) require contracting authorities to assess tenders differently?

The answer to (i) is that they do – up to a point, and the answer to (ii) is that they may do – but perhaps due to reasons other than the new definition of MEAT.

MEAT assessment

Typically, MEAT, which comprises quality and price, is assessed by (a) scoring the quality (Q) element of a tender; (b) scoring the price (P) element of a tender, and (c) adding Q and P to reach an overall score.

Both Q and P are expressed in percentages, and therefore so is the overall score. A comparison is then applied between all the tenders and the highest percentage is the winner. Nothing could be simpler.

Is this assessment approach still appropriate under the 2015 Regulations?

MEAT under the 2015 Regulations

Whilst the 2015 Regulations do not alter our understanding of MEAT – it is still not the lowest price with a fancy label – there is one change that may have implications for practitioners. And in order to appreciate the change it is best to consider the relevant regulation:

“67.—Contract award criteria

2) A contracting authority must identify the most economically advantageous tender on the basis of the best price quality ratio, which must be assessed on the basis of criteria linked to the subject matter of the public contract in question and must include the price or cost, using a cost-effectiveness approach.” [author emphasis]

To my knowledge it is the first time that Scottish procurement regulations, and art.67.2 of EU Directive 2014\24\EU of 26 February 2014 (the Directive) which informed reg.67(2), use the word “ratio”.

Is it intentional? What does it mean?

There is no doubt that it is intentional but there are two possible alternatives:

- Regulation 67 simply re-states what we all know – that a contracting authority is free to decide what “split” or “weight” (ratio) to apply; for example 70% quality and 30% price; or

- Regulation 67 truly means ratio, i.e. price divided by quality.

The Crown Commercial Service did consider the question in “The Public Contracts Regulations 2015 – Guidance on Awarding Contracts”, and took the view that:

“The concept of “best price-quality ratio” (BPQR) is synonymous with the old definition of MEAT – in essence, BPQR means price or cost plus other criteria and equates to value for money.” [author emphasis]

As we shall see, it is perhaps a little premature to state that to proceed with Q + P “equates to value for money”.

The Crown Commercial Service continues in the same vein by stating that:

“So although there are superficial changes in terminology, contracting authorities may be reassured that longstanding flexibilities can prevail in practice.”

One thing is certain — if the second alternative is correct, then translating prices into mathematical formulas, some of which are fundamentally flawed in any event, must surely be a thing of the past (see Kiiver, P and Kodym, J, 2014, “The Practice of Public Procurement — Tendering, Selection and Award”, Intersentia, Antwerps; Moreau, P, La question de la régularité de la méthode proportionnelle d’évaluation du critère du prix, Public Contracts and Procurement No.12, December 2014, study 11 (étude par Pascal Moreau doctorant en droit public à l’université de Poitiers — capitaine de police chargé d’enquêtes en matière de corruption en marchés publics); Lavér, J and Larsberger, O, “The Art of Identifying “The Most Economically Advantageous Tender”—The Use of Relative Evaluation Models in Public and Utilities Procurement”, April 2012; and Bowsher, M, QC, “Random Effects of Scoring Price in a Tender Evaluation”, Practical Law Public Sector Blog, February 2015.

So what is MEAT?

My first proposition is that MEAT, which comprises quality (Q) and price (P), must be assessed as a whole. If correct, we need to ask whether Q + P is the best arithmetical means to accommodate both elements, Q and P, to achieve, as a whole, the concept known as MEAT, all with a view to achieving value for money.

To date, as we have seen, this has mostly been achieved by Q + P. This may be incorrect as Q + P is to proceed on the assumption that MEAT can be broken down and re-assembled, or put back together, by way of an addition – this is just as incorrect as it would be to proceed by way of a subtraction.

It is interesting to note here that financiers, when assessing the financial health of a business, proceed by way of financial ratios; for example “EBITDA margin” – EBITDA being earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation. Once EBITDA has been calculated it is then divided by the total revenue. Financiers take the view that this method assists in ascertaining the true relationship between operating expenses and profits – and the higher the margin the more financially viable the company is.

I also take comfort from the Oxford English Dictionary definition of ratio:

“The relation between two magnitudes in respect of quantity, esp. as determined by the number of times that one contains the other”.

Taking another dictionary example: “if a box contains six red marbles and four blue marbles, the ratio of red marbles to blue marbles is 6 to 4, also written 6:4.”

The above proposition is very different from the proposition of how many marbles there are (ten). However useful that answer may be, it is not what we want to know or consider when we assess MEAT in the context of tenders. What we really want to know is how much Q there is for the P due to be paid.

Do, or why, “ratios” work?

Some academics (Kiiver, P and Kodym, J, op. cit.) “The Practice of Public Procurement — Tendering, Selection and Award 2014”. Intersentia – Antwerps) view ratios as a way forward because a ratio allows a contracting authority to evaluate, pound for pound, what it gets in quality.

The authors also say that “the basic principle to calculate a tender’s value for money is to divide, quite literally, value by money. In other words, the quality score gets divided by a tender’s price offer”. By way of illustration the authors set out the following working example:

How do we interpret the above … and who succeeds? This is what the authors have to say:

“A is the cheapest and offers 5 quality per euro. B is more expensive, but its higher price is more than compensated by its higher quality. It means that, compared with A, its price increased but its quality grew faster. C is even more expensive, but here the price is not justified: it offers less quality per euro than the first two tenders. D offers the same value for money but in a high price range as A does in a low price range. They are tied: in order to win, D would have had to offer an even higher quality than it did, or a slightly lower price than it did. The final outcome is that B wins. Not because it is the cheapest (it is not), nor because it offers the most expensive luxury (it does not), but because it offers the most quality per euro. C loses so badly not because it is so expensive, but because it hardly offers any additional quality for each additional euro it charges.”

P / Q or Q / P?

Readers will no doubt have noticed that the 2015 Regulations, and the Directive, do say “the best price -quality ratio”, not “the best quality-price ratio”. Which is which?

Using P / Q leads to the lower (not necessarily “lowest”) score winning the bid, whereas Q / P leads to the higher (not necessarily “highest”) score winning the bid – so the outcome should be the correct one either way. However, Q / P is more plausible and a clearer mechanism to show quality per £.

In this sense it is worth noting that it may be more customary in English, as it is in German, to use "price-quality ratio", whereas in French the term used is "rapport qualité-prix", which seems to make more sense. So, at the risk of being accused of bias and favouritism, I will go with the French on that one!

Issues

The use of ratios however raises an important matter – that of commercial confidentiality. Are contracting authorities obliged to disclose the prices submitted by bidders given that the evaluation of a tender is based on quality (Q) divided by price (P) (not Q + P where P is expressed as a percentage – meaning that the prices are not disclosed, just the percentages)?

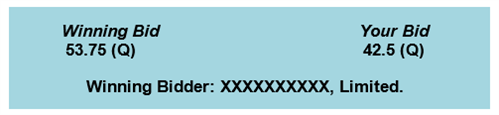

By way of example, I came across the following (edited) award letter in the context of a tender that stated that Q divided by P would be applied:

Although only the quality score was disclosed (as above), whilst the prices were not, Your Bid can of course calculate its overall score as it knew the price it submitted.

But what was the Winning Bid’s overall score? How did it compare with Your Bid and of course how does Your Bid assess its relative merit? Does Your Bid need to take the contracting authority’s word that the Winning Bid was the most economically advantageous tender? If so on what basis?

In addition, is the contracting authority not in breach of its transparency and non-discrimination legal obligations as well as having treated economic operators unequally? In the above case, following a challenge on breach of transparency and discrimination, the contracting authority cancelled the tendering exercise (without, to be fair, disclosing their reasons).

The 2015 Regulations

Before we can answer the questions I raised we need to analyse what legal requirements are imposed on contracting authorities when advising tenderers of the outcome of a tender. For as we all know, contracting authorities are legally bound to disclose a certain amount of information about how it reached the conclusion it did.

What is at stake here is of course tenderers having asked for some of the information to be kept confidential. So what is the legal status of commercially confidential information in light of contracting authorities’ legal duties to be transparent, non-discriminatory and fair under the 2015 Regulations in the context of most contracting authorities being subject to the freedom of information legislation? How do we reconcile all these seemingly conflicting interests and legal obligations?

Regulation 22 of the 2015 Regulations

“22.—Confidentiality

(1) A contracting authority must not disclose information forwarded to it by economic operators which they have designated as confidential, including, but not limited to, technical or trade secrets and the confidential aspects of tenders.

(2) Paragraph (1) is without prejudice to —

(a) any other provision of these Regulations, including the obligation relating to advertising of awarded contracts and to provision of information to candidates and tenderers set out in regulations 51 (contract award notices) and 56 …;

(b) the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002;

(c) the Environmental Information (Scotland) Regulations 2004; and

(d) any other enactment to which the contracting authority is subject relating to the disclosure of information.”

Clearly, reg.22(1) is on the side of bidders’ right to have declared confidential information to be kept confidential. However, the right to confidentiality is subject to a raft of other obligations whereby disclosure may have to be made.

Setting aside the mechanical aspect of contract award notices, key disclosure obligations are contained in reg.51(2) and (6):

“51.— Contract award notices

(2) A contract award notice must contain the information set out in Part D of Annex V to the Directive.”

(6) A contracting authority may withhold from publication information on the contract award or the conclusion of the framework agreement where the release of the information —

(a) would impede law enforcement or otherwise be contrary to the public interest;

(b) would prejudice the commercial interests of any person; or

(c) might prejudice fair competition between economic operators.”

Part D of Annex V referred to in reg.51(2) is interesting in that it details all that an award notice must contain. For current purposes the most interesting part is:

“13. Value of the successful tender (tenders) or the highest tender and lowest tender taken into consideration for the contract award or awards.”

The only exceptions therefore to the information that must be disclosed are contained in reg.51 (6). And assuming that contracting authorities may take the view (i) that disclosing “values” of tenders may overcome tenderers’ commercial interests and may not prejudice fair competition between the tenderers, and (ii) that tenderers, by agreeing to tender, may tacitly have agreed that they can only insist on confidentiality “up to a point” (for example trade secrets), the one main recourse to preserve confidentiality are those contained in the exemptions set out in the freedom of information legislation.

Such attempts have been made in the past with mixed success as far as tenderers were concerned – see the Information Commissioner’s Decision Notice No: FS50225629,10 March 2010.

Conclusion

Generally speaking, the direction of travel in the context of tendering for public contracts has been towards more accountability and transparency. This is borne out by the freedom of information agenda combined with the transparency, proportionality and non-discriminatory requirements in public procurement rules.

In view of the above I think it may be safer for contracting authorities and economic operators to proceed on the basis that, unless strong and compelling reasons can be advanced for commercial information not to be released, more information than not will be released – if not as soon as an award is announced, then at least within a reasonable period of time.

Lastly, I have shown elsewhere that some price scoring formulas encourage a race to the bottom. Were a contacting authority to release prices in award letters (having alerted tenderers that it would do so and thereby potentially removed possible legal challenges) then we may witness a similar race to the bottom. That, for a number of reasons, would be a pity, but only time will tell whether the legal requirements of transparency, non-discrimination and fair treatment of economic operators will overcome their right to commercial confidentiality as regards submitted tender prices.

If you have any questions in relation to procurement, and this topic in particular, please do not hesitate to call BTO on 0141 221 8012.

Look out for my next eUpdate in this series on “Tenders and the (S) 2015 Regs”.

Links to previous eUpdates:

In previous eUpdates: Price Scoring - Getting it wrong? / Price Scoring, Fair Work Practices...and the Living Wage, I discuss relative and absolute price scoring formulas – the disadvantages of the former and the potential advantages of the latter. I also cover a price scoring formula that may assist in promoting fair working practices. In Price Scoring - Does the perfect formula exist? I identify components formulas should ideally include (or not) in order to adhere to the Treaty principles of transparency and non-discrimination.